Erasing All Doubt of Greatness

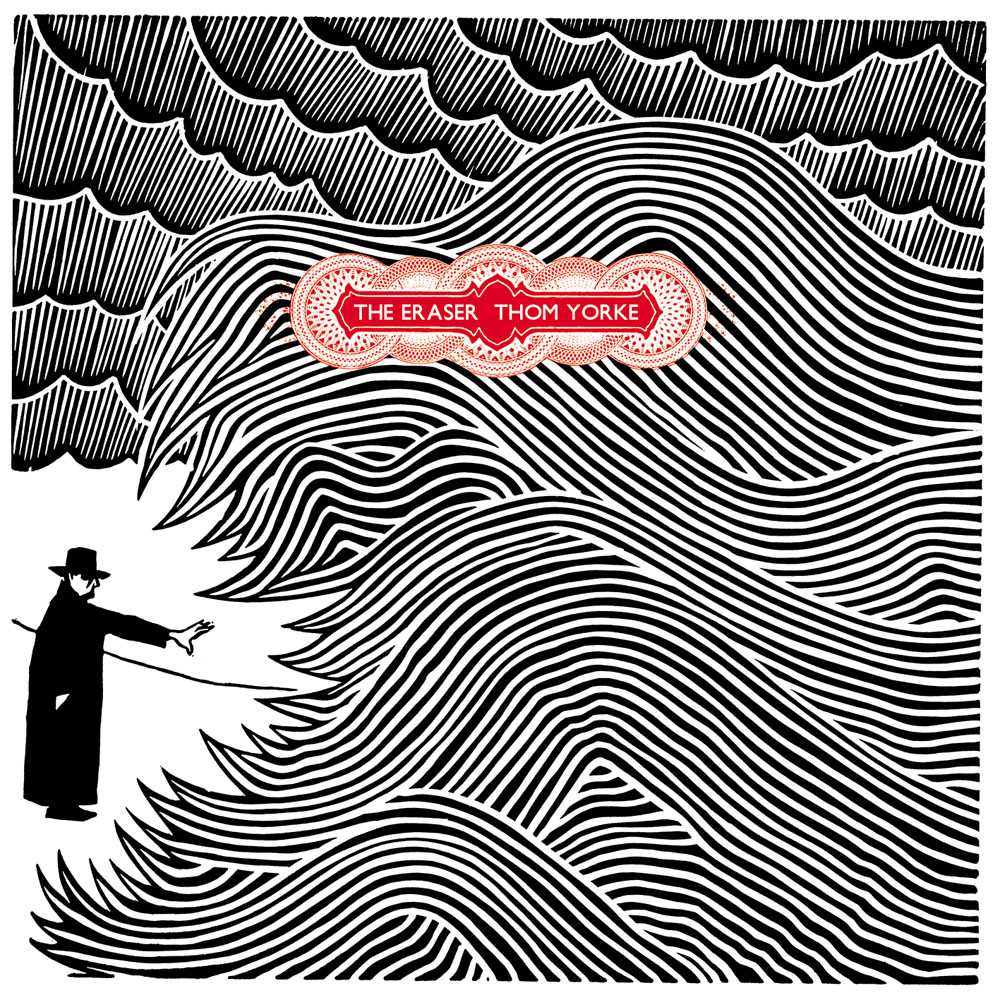

On a normal day, if normal really exists for him, Thom Yorke is the lead singer/songwriter for the British band Radiohead. Originating from Abingdon, Oxfordshire, the band debuted their first solo, “Creep,” in 1992. Initially, the song was unpopular. After several months, the single finally became successful, propelling the band into world-wide fame. Rolling Stone magazine declared the band number 73 on their list of “Greatest Artists of All Time” in 2005 and the following year, Thom Yorke released his premier solo album, The Eraser.

The first track album lends its name to the album, and opens with pulsing chords on a piano. A few moments later, Yorke adds digital drums followed closely by his own soothing voice. Due to his higher range and thick British accent, I find it nearly impossible to understand the lyrics. But that suits me fine-here they are merely an accompanying instrument. The piano continues to pulse its syncopated chords as more instruments are added to the mix. All are digital, a theme maintained throughout the album. As the track closes, the instruments seem to fade out, until the song takes a second life for its finale. Then they do fade out, until the listener is left with only Yoke’s voice, lyric-less.

Unlike the first track, the second track, “Analyse,” doesn’t take its time with a build up.This track consists primarily of a trio between voice, percussion, and piano. The lyrics seem to drift steadily along, while the keyboard is again pulsing minor chords. It is the percussion that provides the energy in the track. About halfway through, Yorke adds more digitally added effects, creating tension. Yorke ends the song with a decrescendo of an electronically created note, adding to the mysterious mood of the piece.

The next track, “The Clock,” is driven from the start by electronic drums. Shortly into the song, Yorke adds a keyboard, along with his own voice, this time almost lethargic, contrasting the forward rhythm of the rest of the instruments. Contrasting himself yet again during the coda, Yorke hums to the end of the song, at a faster, more exciting pace than the previous lyrics.

Track four, “Black Swan,” confuses me: It is so far the most techno-oriented song Yorke presents to his listeners. Yet, a guitar is clearly present in the background. This theme of contradiction is maintained throughout the album, and it is that which entices me so. On this particular track, Yorke layers his voice, but he leaves it untouched by any other computer aid.

A fax-machine like beeping dominates my attention in “Skip Divided,” along with a richly synthesized bass line. Together, the beeping and Yorke’s voice grow in urgency. The beeping turns into a rapid staccato as the song grows in force and Yorke begins to blend his words together. I find this particular song eerie and intimidating, especially when listening to Yorke’s nonsensical lyrics as it draws to a close.

“Atoms for Peace” is the most upbeat track on the album. Again, this song features a synthesized bass line, although this time, it bounces from beat to beat, creating a buoyant mood. Like Radiohead’s famous song, “Paranoid Android,” the lyrics here imitate schizophrenic word salad. The only distinguishable theme to them is that of love.If this is a love song, it is an odd one.

A rolling percussion line that reminds me of a train introduces the seventh track, “And It Rained All Night.” As the synthesized brakes are put on, the bass line is entered. The opening lines of the song confirm my suspicion, creating the image of a New York subway. Yorke expands this imagery, revealing to the listener that his song is about a secret agent planting a bomb. A little over midway through the track, the train returns, perhaps this time to carry the bomb into the heart of the city. I cannot understand Yorke’s metaphor here, but the throbbing of the bass heightens the suspense of the song, as it transitions into the next track.

The penultimate song on The Eraser, titled “Harrowdown Hill,” is, in Yorke’s own words, “the most angry song I’ve ever written in my life.” “Harrowdown Hill” tells the story of the death of British UN weapons expert Dr. David Kelly. Dr. Kelly himself was part of one of three inspection teams sent to Iraq to look for WMDs. His assignment was to view and photograph two alleged mobile weapons laboratories. Unsatisfied, Dr. Kelly took his findings first to The Observer, which quoted him anonymously, “They are not mobile germ warfare laboratories. You could not use them for making biological weapons. They do not even look like them. They are exactly what the Iraqis said they were – facilities for the production of hydrogen gas to fill balloons,” and then to the BBC. Unfortunately for Dr. Kelly, the BBC revealed him as their source. In July of 2003, Kelly made an appearance before the Foreign Affairs Select Committee for cross-examination. Two days later, Dr. Kelly was found dead in the forest known as Harrowdown Hill. The Hutton Inquiry found that it was suicide, although when paying close attention to the lyrics of “Harrowdown Hill,” it is clear that Yorke believes the death to be murder. Yorke states his opinion through lyrics such as “You will be dispensed with/ when you’ve become inconvenient,” and “Did I fall or was I pushed?/ And where’s the blood?” Yorke goes on to blame the Ministry of Defense with the lines “So don’t ask me/ Ask the ministry,” and “Can you see me when I’m running?/ Away from them.”

All in all, I find Thom Yorke to be an abstract musician, both in his work with Radiohead and on The Eraser. It is exciting to observe an artist push the limits of limits of what is acceptable in a song, and critique his government when doing so. Yet, Yorke does not loose his professional sensitivity, saying “I’m not gonna get into the background to it, the way I see it… And it’s not for me or for any of us to dig any of this up.” Cheers, Thom Yorke.